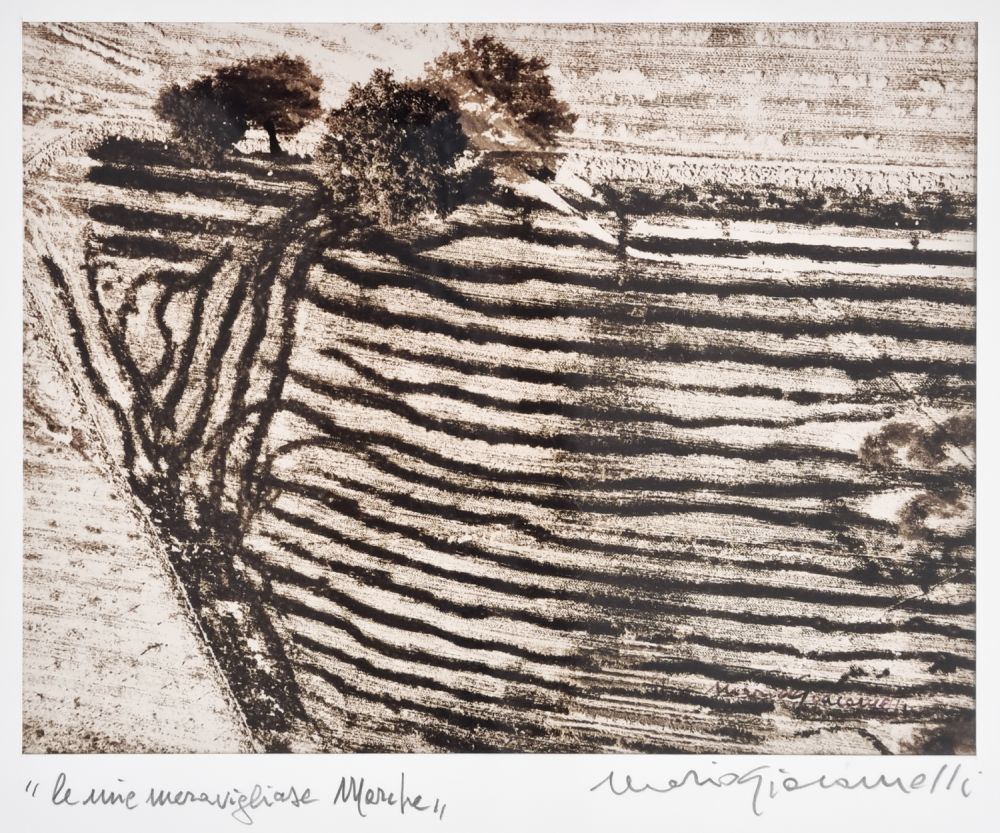

"le mie meravigliose Marche"

gelatin silver print, toned

signed on recto, titled and signed on passepartout

These are aerial photographs taken from a Piper plane. Giacomelli’s photographs from this period are high contrast: through abstracting and essentialising forms, they emphasise the importance of signs. The crux of Giacomelli’s approach is (as we read in his notes for his test prints) retaining the vitality of the material.

"A landscape is a means of total expression, where I feel nature upraised and time thrown into traumatic flux. It reduces space to a single emotion. It’s an extension of my existence, its rhythm and repetition filtered through a flow of images. I don’t reproduce the landscape, but its signs, these memories of “my own” landscape. I don’t want it to be immediately identifiable, I would prefer it to recall certain signs, to recall the folds or furrows in the palm of one’s hands. This vision of agriculture used to fascinate me because I saw the landscape as a pure and powerful means of documentation, with everything still to be discovered, lived. But then I realised that I was in fact photographing my inner self, that through the landscape I found my soul. […] The land has its own signs, its own folds, and it was calling out to be photographed, or so it seemed. Its signs presented themselves so that the soul could relish them, they were inner signs reflected in creative action, in constructive destruction. The land became a voyage of desire, sensitivity, penetration, and orgasm because it didn’t just echo the visible world. Perhaps I never really photographed the land: I simply loved it."

(Mario Giacomelli, handwritten notes 1990s, Courtesy of the Mario Giacomelli archives)

Stories of land and raising awareness about nature (1955-1994)

My primary interest has always been man. Even landscapes, for me, are a portrait of the men who create them." These are fundamental words to understand Giacomelli man and artist. Who in the interview given in '90 to Giorgio Negri thus continues, "For me it does not matter the country, the place that is represented, but the emotion, the contact that is created between me and the land. So the land is more important than the landscape per se. Of course these feelings arise from the landscape, from its construction, from the whites and blacks that I read in it.But they also arise because I know who 'makes land,' who works, and I know the contact that is created between laterra and the farmer. That is why the earth is also seen as the folds of the farmer's hand, of the worker: the earth is the signs of the farmer."

The land is thus charged with multiple, even contradictory valences: it is present and past, at one and the same time, with breakthroughs into the archaic, in the centuries-long continuity of rural life; it can be a generous mother or a stepmother; beauty and charm but also a place of toil and work: a necessary and fundamental point of confrontation for the man who tries to enslave it to his own needs. Yet this contraposition was once configured in forms of respect (even religious) and balance, preserved unchanged over the centuries. Today, the transformations that have taken place in the last thirty years," writes Giovanni Mottura, "seem to authorize the hypothesis of a break whose radicality has very few precedents in modern times, at least inItaly." It is the end of agrarian culture. "Photographing one grasps this evolution, so much so that over time I became more abstractand that now I can't do any landscape. Giacomelli's photography thus experiences this ambivalent relationship: on the one hand, the suggestion of the good earth worked by the farmer, "of an impossible beauty, as if it were a "lace" around his house; on the other hand, the anger for a world that inexorably disappears overwhelmed by technology (especially in the cycle The Dying Earth).

As for the formal aspects, Giacomelli achieves some of the highest, if not the highest, results of his production: in the extraordinary effectiveness of the layout cut (a photo must be a little 'ruffian' in technique or cut, to remain in your mind), unhinging the depth of field, he resolves in poetic two-dimensionality the painting of the earth. It becomes the great page of a notebook where the first man, almost unconscious, has traced his marks, where the man-farmer continues to write his abstract, very concrete writing. That is why there is always a tree or a house, "to give a reference to the proportionsof the landscape. That is, this land that you see as beautiful is not a mark I made in the sand, but look!...there is a house, aprecise point that also gives you the measure of how many miles this land is beautiful.

A beauty made all the more fascinating by the pictorial-lithographic qualities of the image (Giacomelli's training as a typographer!), which,simplifying the visible, burns contrasts, plays poetically on blurring and blurring, on the grain that flakes off in burnt blacks lost in overexposure, or in faded white: so much so that the element of nature explodes into pure visionaryness.

(from the book: Mario Giacomelli. Fotografie 1954-1994, 1994, p. 109, translated from Italian with deepl)